How many times have you posted something like “Got the flu” or “Broke my leg” on Facebook or other social media site?

You don’t know? You should, because your health insurance company probably does.

Evidence that insurance companies are scanning social media sites is mounting. My Twitter friend Mark D’Cunha shared a ScienceDaily.com article about Johns Hopkins researchers who are tapping the firehose of tweets for tracking flu outbreaks. If the medical community is looking, you can bet insurance companies are taking a peek, too.

A law professor at the University of Washington is also suspicious that our individual posts are making their way into the hands of insurers. In her article on the legal punditry website Justia.com, Anita Ramasastry cites examples of social media posts being used as justification for decisions to drop members from insurance coverage. One of the more famous cases involves former IBM-er Nathalie Blanchard who was kicked off the disability rolls of Canadian insurer Manulife. The company stated the collection of Facebook pictures Blanchard posted in which she was portrayed as having fun was not the sole factor in its decision to cease funding her depression claim. Notice how Manulife said the photographic evidence was not the sole factor. The underlying meaning: the photos are part of the factors of evidence cited by Manulife in justification of their discontinuation of Blanchard’s benefits.

People seem slow on the uptake that for-profit insurance companies will be using any (legal) means necessary to make their shareholders money. Has social media, with it’s lofty claims of “democratization,” erased our memory of the cold machinery of capitalism? Of course insurance companies would run algorithms on your public social updates. If Blue Cross hired me tomorrow, I’d tell them the same thing. Your social media updates contain the data they’d have to pay or subpoena you for in decades past; you’re giving it to them for free and without a summons to appear in court.

Ms. Ramasastry cites a report by big insurance-brokerage firm Marsh & McLennan that was released in October 2011. The report outlined how insurers could look at lifestyle choices, proof of risky behavior, and a person’s Facebook Likes to determine their risk level as an insured member. She notes that insurance fraud investigators are already using social media to uncover proof for cases against claimants. It follows that they will also use the social data to determine if a person would be a fit client.

This concept of screening potential customers isn’t new. Demographic research has driven the insurance industry for centuries. Technologically, it wouldn’t be hard to design and code an algorithm that collects the number of times you post “I’m sick” within one year’s time and contrast that to your friends’ posts or other relevant data. Details are nuanced out of data sets by comparing and contrasting different data points. This is what scientists, especially psychologists, sociologists and public health researchers are trained to do.

In a few years, not-necessarily-college-educated data journalists will have the skill and access they need to conduct the data gathering themselves. Every human resources department will have a data journalist or “growth hacker” on staff. Their code will not only run a credit check on you but a similarly-designed “health check” as well. And why not? If HR can predict with pretty good accuracy how many sick days you are going to take, they will do it. If the hiring decision comes down to you and another candidate who seems healthier and less of a party animal, I suggest you start peddling that poor profile elsewhere (and consider scrubbing it clean first).

People are under some illusion that social media posts are protected communication. It is the same illusion I encountered while working as a systems administrator; associates held beliefs, almost to the point of superstitious, that their email correspondence was protected and was not to be monitored by their employers. Just like now, that belief was not based in fact or law. Corporate email is not the US Postal Service, and neither is Facebook.

The courts in Quebec are still working out the Blanchard case, 2+ years later. In the US, it wouldn’t take as long. An American citizen, in regard to the privacy of public social media postings, doesn’t have a broken leg to stand on.

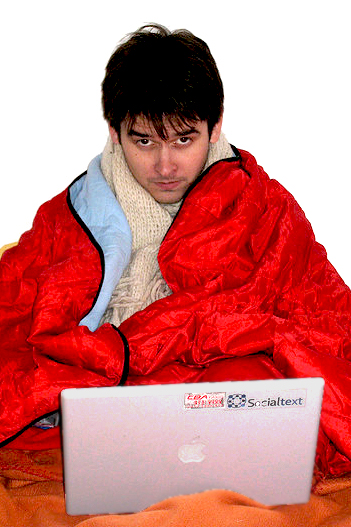

Photo Credit: Alicia Nidjm at Flickr

Comments on this entry are closed.

I happen to work on an online class system. Several of our clients have brand names for their site. I happen to watch for these names on Twitter. It was intended as a thermometer for performance issues. Somehow I also saw messages about the students bragging about cheating. Shocking that 19 year olds would have such bad sense.

Ezra, that is shocking. What will you do with that info?

First, I screen captured the postings. We knew the students would delete them when they figured out the school was on to them. Next, we contacted the distance learning administrators for the school. Our advice was to monitor and investigate quietly. Sure enough the students continued to brag, solidifying the case. I dug up plenty of information from the database and web server logs on their activity.

It was obvious when the students were confronted because all the posts were deleted. 🙂